Jack Spencer No.1 Squadron S.A.A.F.

Members of my family and others have asked me to record my wartime experiences. At the risk of boring others that might read this, I have included a brief record of the various training courses that we went through to become pilots in the SAAF. The curriculum was standardized throughout the Commonwealth and later, I think in the USA. If my memory is correct, it was known as the “Air Training Scheme”. Later many RAF pilots were sent to South Africa for these courses at the expense of the many aspiring South Africans who couldn’t be accommodated. I suppose this met the needs of the war effort, but of course, as I heard later, very disappointing for many. It seems like I must have been just in time to get onto a pilots course.

I enlisted, aged 19, in Durban on 5TH May 1941, to hopefully become a pilot in the SAAF. After a strict medical I was given a one-way ticket to Pretoria and eventually arrived at Roberts Heights. After waiting about a week for amassing of 100 recruits, we were posted to Lyttleton as “Air Pupils”, issued with uniforms, which included a light blue cap band. We were then told that we were the lowest form of life – and for the next 3 months were treated as such!

ITW ( Initial Training Wing) was basic training and consisted of squad drill all morning and lectures in the afternoon. Our drilling instructors were mainly NCO’s from the SSB (Special Service Battalion- formed during the depression). They were fine types behind their facades of bullying task masters. I rather enjoyed this period of acquiring strict discipline and I am sure most of us found the learning fun. Most air pupils were school leavers. I remember one by the name of Stan Cloud from East Rand somewhere, whose irate and indignant father came and pulled him out – he was only 16 years old! I think he had forged his father’s signature.

After passing exam’s and some leave the 45 survivors were posted to ATW (Advanced Training Wing) This course consisted only of lectures, lasted about 2 months, during which time we weren’t such “low lifes” and had to write more exams. After some more home leave I was posted to EFTS (Elementary Flying Training School) at Potchefstroom. Course no. 5, housed in the Artillery camp.

Flying at last! Started on Tiger Moths on 25th November 1941. This time it was flying in the morning and lectures in the afternoon. What a job to keep awake during lectures! We were no longer “Air Pupils”, but “Pupil Pilots” with a different cap band.

SAAF Tiger Moths

I soloed in 10 ½ hours. What a wonderful little aircraft the Tiger Moth was and I thoroughly enjoyed the course. After 86 flying hours the course ended and I was assessed to continue training as a pilot.

Some poor guys didn’t make it and were “washed out,” as the term went. However 12 of

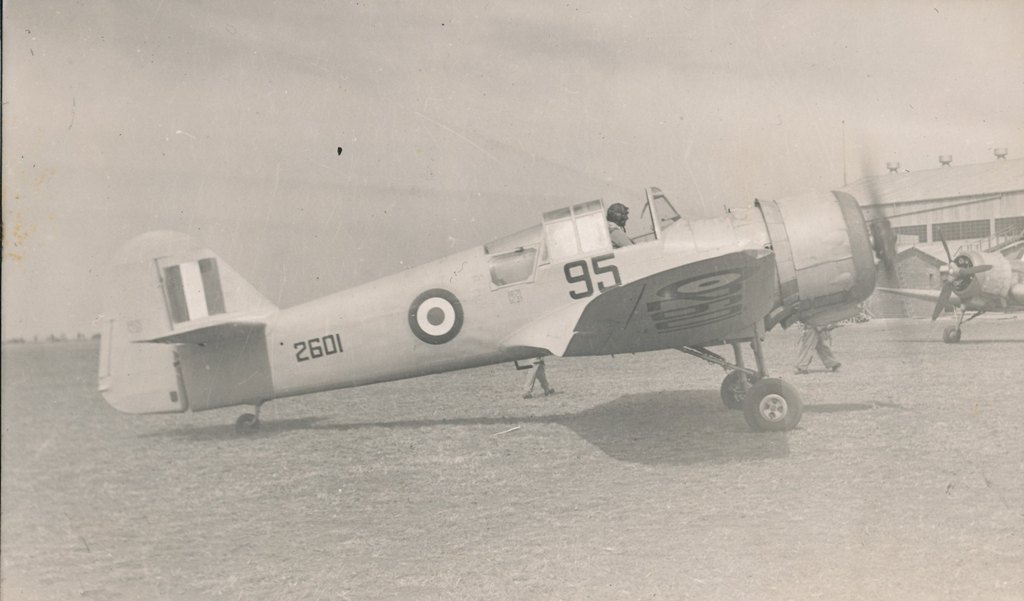

us were posted to Vereeniging, No. 22 Air school – SFTS (Service Flying Training School) course no.15, joining pupils from other EFTS’s and started flying Hawker

Hinds, Harts and Audaxes. These rather antiquated bi-planes were powered by Rolls Royce Kestrel 600 hp. engines and were great to fly.

SAAF Hawker Hinds

After qualifying on 3rd July 1942 after 214 hours total flying time we were given home leave…..wow! Three weeks in Durban and a pip and wings up!

We had been trained as medium bomber pilots and had to convert onto twin engine Oxford Trainers at 26 Air School, Pietersburg, which we started on 28th July 1942 and completed on 3rd September 1942. . They then, much to my disappointment, sent me to CFS. (Central Flying School) at Bloemfontein, on an instructors course. I managed to fail that, and they then gave me 2 options - Staff pilot in the Cape, or conversion onto fighters, & up North. Well, what a pleasure!

Oxford trainer

After a short conversion course of 16 hours onto Miles Masters at Bloemspruit, I was assessed as “above average” Group 1 Pilot on 28th January 1943. Next – awaiting embarkation to Egypt as a passenger in a Lockheed Lodestar. Waterkloof to Cairo took 5 days – one day & night lost to a sand storm in Sudan – a place from hell, called Malakal.

Miles Master

Lockheed Loadstar

In February 1943 I arrived in Cairo where I met up with ex fellow pupils who were green with envy, I being the only one of our course to end up on fighters. They had been to Bomber OTU in Kenya.

I had to wait until 16th March to start at 73 OTU. (Operational Training Unit) at Abu Suier, (Suez Canal) putting in 46 hours on Harvard’s & Spits. Course ended 17th April.

73 OTU Spitfire

We then had to hang about at Castel Benito, near Tripoli getting in a few hours flying at 244 Wing training flight. This carried on for months, waiting for posting to 1 squadron – 3 of us were due for there. We got up to various activities and I remember sharing a tent with an RAF flying officer – Parbury, - waiting to start his 2nd tour (to a RAF squadron). The only booze available was gin & brackish water – I couldn’t stomach it, but the awful taste didn’t worry Parbury. He would return to the tent later being very talkative. His tales of his escapades in Cairo were very entertaining, and I often wondered whether he survived his second tour.

Three of us were awaiting posting to 1 Squadron who were part of 244 RAF Wing.

As the war was getting up

1 SAAF was due to leave 244 RAF Wing (after having had a wonderful period with them) and join 7 SAAF wing later in Italy. 1 SAAF would still take the fighter role, for example, top cover, escort to bombers and bomb line patrols and the occasional strafing missions when required. The other 7 Wing squadrons were to carry out dive bombing and strafing missions.

It was really great to be in a fighter squadron at last. We had a very young squadron doctor in Sandy Brown who could play the piano and guitar, we had a Cecil Golding who was a super jazz pianist and I also played the squash box. The atmosphere was a really happy one of bantering, jokes and leg pulling and was something to be treasured. Sandy was such a caring and kind doctor, so when at night in the mess, someone would complain of stomach troubles he would answer: “DRINK”, or for a cough; “SMOKE”. We all knew it was his humour again. I must say as an oldie now, the jokes and antics appearing through this story, now seem a little silly, but please remember, we were very young and in an exciting situation.

Dr Sandy Brown

Cecil Golding

I really can’t forget the wonderful music we had in the Squadron from the BBC. The greatest of course was the American band of the AEF (Allied Expeditionary Force) which of course was the Glenn Miller Orchestra.

Then there were Tommy Dorsey, Jimmy Dorsey, Benny Goodman, Artie Shaw and Harry James. Of course there were the British bands – eg. Geraldo (British band of the AEF), Carol Gibbons etc. How about the vocalists such as Crosby, Eberly Brothers, Bygraves and of course the up and coming Sinatra who had yet to become so well known and – dare I say it – “famous”. Luckily I still have a lot of it on the (now) old audio tapes, which are quite good enough for me.

On about the 6th October I was sent to a field hospital back in

On Christmas day 1943 we were doing a bomb line patrol at the Sangro river in appalling weather – cloud down to 1000 ft. We were recalled and on the way back my engine started overheating and cutting out, due to a glycol leak. My options were to try and put it down or bale out. As we had recently lost Bert Staples trying to force land in a dry river bed, I took the option of bailing out, but you don’t bale out of a Spit at 900 ft, however I had no option and was over the waves. As I left the aircraft my legs hit the tail plane and I thought they were broken. A split second after I pulled the rip cord I landed in the waves and managed to release my ‘chute and with it my inflatable dingy because of the strong wind taking me out to sea. I still had my “Mae West” to keep me afloat.

There was a unit of S.A. Engineers camped on the beach who had witnessed all. Two of them stripped and swam out to me in the freezing waves, and were surprised to find me there, as they had seen a black dot disappear into the splash of the aircraft going in. An amphibious jeep was sent out, which we all climbed onto. It then sank, and we were back to square one! Someone had apparently forgotten to shut a stop cock or something!

A second Ducw was sent out, and we finally reached shore – where I was given some dry clothes and a stiff shot of Issue brandy. I learned later that the two Sappers were “Mentioned in Dispatches” for their fine efforts. I was returned to the squadron and joined the Xmas lunch being traditionally served to other ranks by officers. I was given a loud cheer by all, as I hobbled in. According to Sandy, I had bruised the bones in my legs and was given a week off flying.

Although the Luftwaffe was virtually non existent in that theatre, we did occasionally run into them – once 4 of us clashed with 12 FW 190`s and ME 109`s and damaged a couple. Another time 6 of us took on 20 + 190`s and whilst chasing 2, I was jumped by 2 FW 190`s who fired on me. I ducked, and they missed and it was over. They had in the meantime shot down and killed my friend Johnny Oates, who had been flying next to me. I was No. 2 to Col. Loftus and Johnny was No. 2 to Dave Hastie. We also did sorties across the Adriatic into Yugoslavia, which I didn’t enjoy much.

Col. Doug Loftus

Dave Hastie

On about the 2nd June 1944 Butch Freeman and I were given a weeks leave at an R.A.F. “Rest Camp”. Well this “Rest Camp” turned out to be the Hotel Cocumella in Sorrento. After living in tents for about 18 months, it was wonderful, so well run and staffed by Ities, who knew their jobs, complete with Palm Court Quintet providing soft pre dinner music with our drinks. The war was suddenly far away.

Butch Freeman

We spent some daylight hours among the seaside rocks and having the odd swim. I heard for the first time “ Come back to Sorrento” being sung in Italian by a man walking in the street – just too beautiful. (Ities break into song any time) One day we took the ferry to Capri, but it was taken over by the Americans, who were almost hostile to us. We managed to do a horse and carriage tour of the island and were shown the home of Gracie Fields. (locked up and deserted) Also the grave of the Swedish doctor and author who lived there and wrote a lovely book about the island and it’s people. Just can’t remember his name. We also did a guided tour of the ruins of Pompeii which was very interesting. Also took in a variety concert in Naples put on by the locals and the artists were top class.

As we were leaving Sorrento we heard about “D” day (6th June 44) and headed back to the squadron at Orvieto via Rome – also full of Americans. (they were everywhere!)

On the 27 June, we were on an armed recce south of Rimini, and after a bit of strafing of m.t. we were returning to base when we ran into very intense and accurate heavy ack ack fire at about 8000 ft.

An 88 mm got me just under and forward of the engine. I heard it, smelt it, felt it and the engine stopped, and the wings were full of jagged shrapnel holes – smoke everywhere. I heard later, that my no.2 Cecil Boyd (killed later on, whilst strafing) had quite a few holes in his a/c. My radio was still working and I called leader to say I had to bale.

Cecil Boyd

This was about 21-00 hours and as I was floating down I could hear rifles and Tommy guns going and prayed it wasn’t in my honour,

I landed on a gently sloping hill, and down at the bottom I saw what seemed to be the entire German army running up, and shooting wildly. I dived under a large bush and presently a guttural “Kom oud Englander”. I went out, and was surrounded by a group with Tommy guns etc.

A short little guy, ( It’s always the short ones!) started shouting about a pistol in a very threatening manner – I think he thought I had thrown mine into the bushes, but I never carried one. As he was about to start beating me up, a Feldwebel came running up and gave him a good German tongue lashing. He then said to me (in broken English), the inevitable, “For you the war is over.” How wrong he was! He then said to me very politely “ Sir, do you need any medical attention and I said “ no, I am ok”. I had lost one of my flying boots when the `chute jerked open, and they later gave me an old pair of Itie army boots taken from a dead Partisan.

In retrospect, had that 88mm shell exploded a split second later, I and not the motor would have got all that shrapnel and on Christmas day, had my chute opened a second later, I would never have survived, and if those 190’s hadn’t missed when I saw those shells flying past my cockpit- same thing! Was it a kind fate or the devil looking after his own.

The memory is fading a bit on what happened next, but I remember being driven in gathering darkness in some kind of small vehicle with armed guards who were more fearful of possible Partisan attacks, than of me.

I was locked up that night and the following day I was shunted about from unit to unit, under guard of course. That night I was invited to dinner with their equivalent of a colonel. It was a pretty meagre meal, and of course the language was a problem. He seemed to be quite well decorated (Iron cross hanging around the neck etc) and did his best to be hospitable.

The next day I remember being driven through Florence and entrained for Germany.

I arrived at the Aircrew Interrogation Centre, possibly 2nd July ’44. I can’t remember where it was – called Dulag Luft. Solitary confinement in a small cell, full of fleas. Our boots were taken away every night. I remember overhearing an American saying to the Goon in a loud voice “ shine ‘em up boy, shine ‘em up.”

After 5 days in this cell (believe me, solitary confinement is not what it’s cracked up to be, especially after the wonderful camaraderie of a fighter squadron.) I was taken up for interrogation. After my demanding that I only need give my name rank and number, the interrogator told me I was from 1 Squadron and even named the O.C. He knew just about more than I knew myself.

A group of “Kriegies” (prisoners) was then collected and for the first time since capture, I had contact with my own. These of course were mostly Americans. Everyone was covered in flea bites and scratched for ever. I had not one flea bite which I thought may have been due to the Jaundice I’d had. I didn’t think my blood was that bad.

In the meantime the Goons had confiscated my watch and signet ring, for which they gave me a receipt. More surprisingly both were returned to me on arrival at Luft 3. We were then given 1 post card each to send to next of kin. I still have this card in which I apologized to my dad for not writing sooner as I had changed my address suddenly and told him not to worry as I was fit and well. I didn’t mention how bloody hungry I was.

This was the first he had heard that I was safe and a POW, so he quickly changed from being grief stricken to highly overjoyed. En route to Luft 3, I was in a coach full of Americans and it was deafening after the “solitary”. They had the urge to tell their stories. I learnt that Yank’s all talk at once and loudly!

Stalag Luft 3 was at a place called Sagan in Poland (but at that time was said to be in Germany), about 60 km’s S E of Berlin. It had 5 compounds - 3 American and 2 British. I of course went into the Brits North compound and first with a room of Poles. They were very nice and gentlemanly, but oh, the language problem!

The bungalows were divided into 16 rooms, designed to hold 6 Kriegies in each. After a short while a vacancy occurred in a room of South Africans and authority from the Goons was obtained for my transfer to them. Needless to say, things started to get a little better.

I would say there were roughly 1500 to 2000 Kriegies in the North compound when I got there. There were of course many anecdotes told to me about earlier days there.

There were some poor guys, who while on patrol in the North Sea with u/s radio, who having not heard the news on 1/9/39, where taken prisoner that day.

The many activities in the camp were strictly controlled by the highly organized Brits. Of course the Kriegies were from all Commonwealth countries and the friendly arguments about the merits and demerits of same were brisk and many.

The summer sports were highly organized and I remember a soft ball league being run by the Canadians. A lot of Sports equipment got through to us courtesy of the Red Cross.

Thanks to the Red Cross we were better off than the Goons (Germans). Cigarettes & tobacco were plentiful for us and were used extensively for bribing the Goons. We had all kinds of illegal equipment, such as a secret radio, digging implements etc. Every afternoon, with look out’s posted, a B.B.C. newscast was read out to every bungalow.

The Goons had “Ferrets” with short metal rods wandering around the compound, mixing with the Kriegies, getting friendly and trying to garner information. We had what we called “Stooges” shadowing them and watching their every move.

Luckily we were in the hands of the “Luftwaffe” and I like to think that our treatment was due to the mutual respect we had as Airmen and not because we were winning the war, at that time.

Hunger of course was the first problem to overcome and I was told to hang in there as my stomach would shrink. Sure enough it did and things started to get better. I don’t think we would have survived without the Red Cross parcels. These came from Britain, Canada and the U.S.A. To us the Canadian parcel’s were the best. That “Hershey Bar” of chocolate in American parcels was tops and a whole Hershey bar was allocated to each Kriegie and probably came up every 10 days or so.

Each man was allocated one food parcel a week and they were pooled together per room and meals were planned accordingly. Goon rations were added when possible, but were wanting, to say the least. I remember their Swede “soup”. Slightly coloured water with a cube of Swede and a cube of horse meat. One item of Goon issue food I will never forget was what they called “fish cheese”. It looked like patties of haddock & quite attractive; but the stench was unbearable. As hungry as we were, we just could not eat it and secretly buried it – just in case the Goons might think we were too well fed! Swedes were actually cattle feed.

I asked about the little black cloth diamonds worn on the sleeves of all Kriegies and was told about the “ Great Escape” and the shocking murder of 50 Kriegies. (4 South Africans). We knew nothing of this in the squadron. The escape was from the bungalow next door to ours.

When darkness came, we were locked in our rooms and shutters closed. Sometimes card games started, or the little gramophone was played, when the rooms allocation came up. Of course most of us smoked at that time and one could barely see the other for the smoke filling the room. At 22;00 it was lights out and we could, thankfully, open the shutters. It may have been a bit later in the summer. If we turned our room’s light out, we could open earlier.

At night dogs were let loose in the camp and extra guards patrolled. At this point in the war (latter part of 1944) our guards were mostly elderly Luftwaffe types and were almost kindly in their attitudes. After the terrible murder of those Kriegies, escape ceased to be a priority and the guards were very unhappy about the murders. At dusk they would have these beautiful Alsatian dogs do all sorts of tricks for us, before starting their duties at nightfall. More about these dogs during the march.

Thanks to the Red Cross, we had a beautiful library and I read some very good books. There were also musical instruments and I think many Kriegies learned to play them. There was a very good theatre set up and we saw some wonderful plays and musicals. (senior Goon officers were invited)

The main occupation was “circuit bashing”, when usually pairs would walk around the perimeter next to the trip wire. (I’m sure, solving the world’s problems) There was a continuous stream of walkers.

I was told a few stories about Douglas Bader, who by that time had been transferred to Colditz Castle. (Punishment) We had a big fire pool with buckets hanging up. In summer the Kriegies swam in it and in Winter, skated on it. Bader whom I believe hated Goons with a passion, would take his legs off and get into the pool and at dusk would float in the middle and refuse to leave. The Goons would start pleading, cajoling, threatening with guns etc and eventually stripping to their underwear and pulling him out. Another trick of his at night was to put his ear against the shutters and if he could hear the ferret listening on the outside, would signal for the lights to be put out and then burst them open and knock the ferret flying. Very apologetic of course. They called it “Goon baiting”.

When winter came of course, the sports changed accordingly. I remember them flooding the sports fields, which turned to ice. Then the ice hockey league was organized by the Canadians and became “Big Time”. I remember that once, for some light relief, they organized a game for South Africans vs Australians. ( both of whom had only before seen ice in a glass). To watch them, just trying to keep upright was hilarious – to see them crawling to get to that disc, (whatever they call it) was something else.

One of the characters in the camp was a Canadian – Steve Watson. He had a sense of humour second to none and loved to get into a “discussion” on conditions in their respective countries. He liked to bait the Pom’s as they sometimes took it a bit seriously. I remember him asking one if he had ever seen a refrigerator and started explaining what it was. Well it came pretty close to fisticuffs. In a discussion with Polly Theron from Kroonstad, Polly got very serious about how they had fresh fish daily in Kroonstad, 600 miles inland. Steve casually replied that they had to hide behind a tree to bait the hook and when they pulled it out, they threw it further than that. Steve was reputed to have trunk loads of watches, Hershey bars and cigarettes and to have the goons in his pocket. He was a few years my senior and has probably passed on by now. I am sure he must have made it big in civvie street.

I must mention what I remember of the wonderful quick heating devises which were in operation dotted all over the camp. They were used mainly for a quick brew up and were made from old Klim tins. A fan geared to a very high speed forced air vertically through the flames, producing a blue flame similar to a primas stove and was very efficient indeed.

About the beginning of September, the

American compounds started to overflow and they started pouring into our

compounds. We had to take four into our room making it ten up. They were pretty

good types, though of course much more extroverted than most of us. One guy,

Jimmy Fore couldn’t have been over nineteen but had apparently been a captain

of a B17 bomber until shot down over France. He was from Little Rock,

A lot of Americans had the unfortunate habit of spitting, so we had to stop walking around barefooted, which p__d us off a bit.

I became quite friendly with an American, Robert H Clark and we used to circuit bash quite a lot, talking about our respective homelands etc. He was a product of WestPoint and was more quiet than average. He was the one who used to bait Jimmy Fore (Hugo!) He was about 4 years my senior and we corresponded for a short while post war. He sure had some tales to tell about his escapades in wartime Britain.

I think Klim tins (powdered milk) part of

Red Cross parcels were the most useful items and were cut up and used for all

sorts of activities. There was an American of Chinese descent and of course he

was known to all of us as Klim Tin. I think it was in January 1945 we could

hear the distant rumblings, during the night, of the Mosquitoes bombing

We knew of course from our BBC news service, that the Russians had reached Poland and were getting close. On 28th Jan 45 around 10:00 pm we were rousted out and told we were marching out in 3 hours time. Some managed to knock up sledges from bunk boards, which were dragged over the iced up roads as we walked. I can’t remember what happened about the stored Red Cross parcels, but I have an idea that they were loaded onto some form of transport and followed the column. Once again I am reminded of what we owed the Red Cross. On arrival at Luft 3 we were given suitable kit if required and I was at last able to discard the awful Itie boots, which were replaced by a wonderful new pair of British army boots and a great coat, among other items. This I am sure contributed to my successful completion of the “march”.

We later learned that it was the most bitter winter in living memory and some chaps had to be left behind en route because of frost bite etc. I believed they were picked up by the following transport, such as it was. We had our first stop at dawn after about 17 kilometers and arrived at Freiwalder at noon in 21 degrees of frost. We found shelter in a loft for the night. We left at dawn the next day for Maskau where we arrived at sunset. I think it was during this trip that the guards had to abandon their beautiful dogs, as the ice was starting to cut their paws. They left them with farmers. As cold and as stressed as we were, it was sad to see the dogs crying and straining to follow the guards, who were very close to tears themselves.

I remember it must have been the second or third day of the “march” when we were really battling to keep going with the driving snow, freezing cold and very poor rations, there was this little Belgian called Joe, in the R.A.F. who had a large well filled kit bag on his back. He was actually walking up and down the stumbling column calling out words of encouragement to the guys to keep going. Where he found the strength to do this, I’ll never know. A small guy again! I only remember his name being Joe – never to be forgotten.

Of course rumours had started by then.

(rumours being a great part of Kriegie life) The strongest rumour doing the

rounds, was that Hitler was going to keep us somewhere as hostages for peace

bargaining. At the start of the march they separated the British and Americans

and we never saw them again. They went south west and we went

We got to Spremberg, probably about 2 days later, when we were loaded into cattle trucks. (40 per truck) We were, I was told, 110 kilometers from Sagan. Later, there was some discussion about how long we were in these trucks. I think it was a few days, others say one day and one night. What I remember most was the crying for water from the poor guys who were dehydrated from the squitters. It seemed to go on for longer than one night. We were offloaded at Tarmstedt where we were searched for hours in the rain, and eventually occupied a disused Naval camp. Although rations were getting very low being in bungalows was a big improvement in our situation.

On April 9th we were on the move

again with much improved weather. By now we were able to watch some heavy air

raids on

At one stage earlier, we actually walked along one of their much vaunted Autobahns, which I now believe were ahead of their time – quite something for those days. I remember one break we had in the grounds of some kind of convalescence hospital for wounded German soldiers. They were sitting out on the grass taking in the sun and most of them were minus legs or arms. It was really tragic, them being so young – mostly teenagers and such very nice chaps. Although there was a very big language problem we mingled with them and unashamedly fraternized with them – in fact gave them cigarettes and whatever else we could spare. We were well aware that we also had our chaps at home in the same predicament, although, I am sure, not so young. I think at that stage we also were reminded of how stupid and obscene war really is.

After crossing the Elbe

on 16th April we rested for a couple of days in a field. We went on

and reached Hamberge. After a day or two we went on and reached our final

destination. This was a large estate between

On May 2nd the guards started discarding their haversacks etc. and disappeared. At around 1:00 pm a British armoured car came slowly up the road. We knew of course that it was the British 2 nd Army. In no time one couldn’t see the car as it was covered in Kriegies swarming over it and yelling their heads off. What a moment in time, especially for the long timers. They had watched the war pass them by and missed all possible promotions etc. etc. Not one of us in our wildest imaginings ever thought of becoming a P.O.W. – killed or wounded maybe – but never this.

We now had to wait for transport to the U.K. which understandably had to be organized and took some time. In the meantime we were allowed to wander around the countryside for a week. Needless to say, we had become expert scroungers and pilferers. I can remember some (to us) wonderful meals we had. I had a beautiful ceremonial sword and scabbard and other items which I can’t remember now. On May 9th we were in convoy, to the nearest airfield, standing in an open truck. An incident that stays in my mind…..the convoy had stopped, near a farmhouse when a family of beautiful white geese headed by a magnificent gander started walking across the farmyard. While we were admiring this scene a South African major named J.P. took up a hunting rifle, which he had stolen and for some mindless reason shot dead this beautiful gander. Well, we were only lieutenants and he was a major, so all we could do was to show our disgust, which we did in no uncertain terms.

On arrival at the airfield we were surprised to see Lancaster bombers awaiting us. We boarded same and had to stand, I think about 20 per a/c. We landed at Guildford and were immediately grabbed by enthusiastic ladies who had us on a bed and gave us a jet of DDT powder up each trouser leg. I wondered what awful diseases, or whatever, they expected us to have after living like monks for so long! We were then sent to join all the other S.A. ex P.O.W.’s down at Brighton – being billeted with several others in a house taken over by S.A. forces. We spent a month in U.K. on leave and what a great month it was – mostly up in London by a very fast and efficient train service (6o miles in 55 minutes and very comfortable too) While walking down the Strand in London with a couple of mates we bumped into a former pupil pilot whom I hadn’t seen since E.F.T.S. and asked what he was doing there. His cap was on the back of his head and he was swaying in the breeze and airily said he was there to fly us home. We had recently been offered a sea voyage home and after seeing John swaying in the breeze, the sea voyage offer became quite attractive. After surviving all those hazards, it was the ocean waves for me! It must have been about June 9th when we boarded the “Alcantara” at Liverpool, that had been an armed Merchant cruiser during the war. She was a 22500 ton ship and was very well appointed. (beautifully panelled lounge, dining room etc) By then I had become friends with a couple of guys and were just starting to feel complacent about our choice when we were devastated by being told that all troop ships were now ‘DRY”, thanks to Monty! Apparently the convoyed troops were the worse for wear on arrival in Egypt, or wherever.

We were about 6 to a cabin and in the bunk

next to me was Donald Grey, a quite well known actor, was a South African in

the British army and had lost an arm in

About two weeks later, out of the morning mist, Table Mountain appeared, it was the most beautiful sight I had ever seen. ( I had never been to Cape Town) I had been away from South Africa two and a half years and felt quite emotional. When we docked and disembarked some nice ladies presented us with the biggest orange I had ever seen. Our excess luggage had been stored in the hold of the ship and when I went to get mine, saw that all the goodies I had acquired in Germany, including the ceremonial sword, had been stolen from the kit bag in which I had naively put them. This brassed me off to say the least.

We then entrained for Durban and what a journey it was. The speed of the train was unbelievable, how it stayed on the tracks, I will never know. I think I was as nervous as on the trips to Yugoslavia! After the first stop (I think it was De Aar) the troops on board got hold of some booze and then the fun started. How there were no fatalities, I will never know. They were staggering all over the train, putting their fists through the windows. Some ended up with severe lacerations etc. We were four to a compartment and I was the only Air Force type there. The others, having been taken at Tobruk. I remember a very drunk private forcing the compartment door open and standing there insulting the officers, accusing them of cowardice and everything else he could think of. This of course was absolute nonsense. They didn’t quite know how to handle it and just stared out the window. I felt quite sad for them.

Well, we finally arrived in Durban on June 27th, exactly 12 months to the day, since my capture. My family were on the Station to meet me and I remember my father being completely overcome. My mother having died when I was six years old. All ex P.O.W.’s were given their discharge immediately – I had about three months leave due and took off. I went to see my employer and he wanted me to start work immediately. When I told him I had three months leave he started telling me that while I was “up there enjoying myself and having a whale of a time, they were having a rough time”; one meatless day a week, no white bread, butter shortages, blackouts etc. Needless to say, he was my ex-boss as soon as possible.

When I look back on the war, I feel that although things got pretty tough at times, there were very many great times, which were most enjoyable. The worst time of course was being a Kriegie or waiting in the desert to get to One Squadron and the best was getting my wings and getting to a fighter squadron like 1 S.A.A.F. also known as the “Billy Boys”.